Patient Death After Inadvertent Infusion of PRN Medication Hanging on Bedside IV Pole

Problem: A prescriber ordered albumin 5% (12.5 grams/250 mL) solution for a patient in the intensive care unit (ICU) who was 4 days post-cardiovascular (CV) surgery and experiencing hypotension due to hypovolemia. A nurse removed a carton from an automated dispensing cabinet (ADC) that contained two 250 mL bags of albumin. Both bags were brought into the patient’s room and were hung on the intravenous (IV) pole; only one was administered to the patient as ordered. Later in the day, the prescriber ordered a second dose of albumin. The nurse used the albumin bag that had been left in the room on the patient’s IV pole. She scanned the barcode on the patient’s identification band and scanned the albumin bag but needed to get new IV tubing. Upon return, the nurse spiked what she thought was the albumin bag and started the infusion. Although the organization had implemented interoperability between the electronic health record (EHR) and the smart infusion pump to allow for automatic programming of the pump (e.g., medication, dose, infusion rate), the nurse manually selected the albumin option in the smart pump drug library, and programmed the solution to infuse over 1 hour, bypassing pump scanning and auto-programming. The nurse did not trace the line from the bag to the pump, or from the pump to the patient, before starting the infusion. Her attention was drawn away from the task due to the need to respond to multiple phone calls/issues, and receiving a second critically ill patient with acute needs. About 30 minutes later, the nurse was alerted by the monitor at the nurse’s station that the patient’s blood pressure had significantly dropped, so she returned to the room. She discovered that a niCARdipine 40 mg/200 mL infusion that had been placed on the IV pole postoperatively, and remained there for 4 days, had been inadvertently spiked and was infusing instead of the albumin. The niCARdipine had been ordered through the postoperative CV surgery order set with parameters to initiate if the patient experienced a systolic blood pressure of greater than 130 mm Hg. Approximately 140 mL (28 mg) of the niCARdipine infused over 30 minutes. The niCARdipine infusion was immediately stopped; however, the patient continued to decline, went into cardiac arrest, and was unable to be resuscitated.

In a previous newsletter article (Latent and active failures perfectly align to allow a preventable adverse event to reach a patient), we discussed how James Reason’s “Swiss cheese” model is used to describe how latent failures (e.g., system failures such as lack of, inaccurate, or incomplete policies or procedures) and active failures of individuals, such as human error (e.g., misprogramming a pump) or at-risk behaviors (e.g., choosing to bypass auto-programming), lead to preventable adverse events. Each slice of Swiss cheese represents a part of the organizational system designed to defend against errors. A hole or gap in one slice of cheese represents a latent failure that may allow an active failure to get through to the patient. However, in the subsequent layers, if the holes are not aligned (i.e., the latent system gaps are addressed), the error may be prevented before it reaches a patient. As with most serious preventable adverse events like this one, many latent system issues (holes in the cheese) need to align perfectly with the active failures of individuals to reach the patient. As you read additional details about the event, notice how a series of latent and active failures can be identified at multiple steps in the medication-use process and consider if these latent failures are present in your organization.

PRN medication (niCARdipine) was stored on the bedside IV pole (latent failure). Historically, the cardiac surgeons’ practice for all postoperative CV patients was to leave the operating room (OR) with a niCARdipine infusion bag hanging on the IV pole "in case" it was needed. Practitioners were unaware of the risks and potential consequences of storing medications not in use at the bedside or hanging on an IV pole.

Lack of familiarity with medication access in ADC (active failure). Some nurses were concerned that niCARdipine would not be readily available should a patient need it urgently. Upon questioning, nurses were unaware niCARdipine was available in the ADC via override should it be needed emergently before the order was verified by pharmacy.

Prescriber did not reassess the patient or discontinue the order (active failure). The niCARdipine order remained active on the patient's profile for 4 days postoperatively without the medication being discontinued or removed from the patient's room when it was not needed.

Medication discontinuation responsibility was unclear (latent failure). Per the organization’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, pharmacists had the authority to discontinue orders for unused continuous medication infusions after 48 hours. However, this was an authority, not a responsibility, and a provision existed that excluded infusions ordered from an order set.

Choosing the wrong bag (active failure). The nurse selected the niCARdipine bag to spike instead of the albumin bag.

Interoperability was bypassed (active failure). The nurse did not scan the barcode on the pump, bypassing interoperability. She noted this was a deviation from her typical workflow, partially due to having to manage multiple tasks at the same time.

Failure to trace the line (active failure). The nurse did not trace the line. There was an expectation for nurses to trace lines with intravascular fluids outlined in the organizational vascular access policy, but the policy was not followed, and line tracing was not routinely performed by nurses.

Inadequate line tracing policy content (latent failure). The vascular access policy stated to trace the line from the bag to the pump, and from the pump to the patient. However, the policy did not specify for the nurse to verify the order in the medication administration record (MAR) and/or to require the medication label to match what is programmed in the pump when performing line tracing.

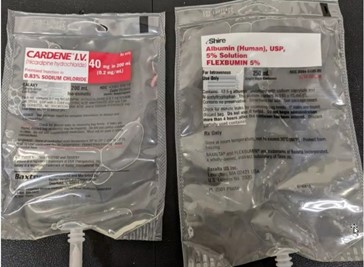

Similar-looking bags (latent failure). Premixed infusion bags of CARDENE (niCARdipine) 40 mg/200 mL by Baxter, and FLEXBUMIN (albumin human) 5% solution 250 mL by Shire, are similar sizes and have red and white labels (Figure 1). Albumin had previously been available in glass bottles, which looked much different from infusion bags.

Culture of intimidation (latent failure). Due to the surgeon’s reputation of intimidating behavior, only a few nurses in the ICU were interested in acquiring the extra skills needed to care for CV surgical patients. As a result, support was less for nurses caring for CV patients. Any behavior that discourages the willingness of staff to speak up or interact with an individual because they expect the encounter will be unpleasant or uncomfortable is disrespectful behavior and often has latent effects on organizational processes.

Low lighting (latent failure). The adverse event described occurred during the night shift, where there was deliberate low-level lighting in the patient’s room to encourage sleep. This normalized behavior can contribute to difficulty reading medication labels.

Perception that only certain nurses could care for CV patients (latent failure). There was an organizational perception that only certain specialty-trained nurses could help care for CV surgery patients. This resulted in an environment where staff did not feel supported when they felt overwhelmed.

Interoperability analytics were not monitored (latent failure). The organization did not have a system or process for nurse managers to monitor auto-programming compliance data, so they were unaware when it was being bypassed.

Safe Practice Recommendations: To minimize errors, evaluate your processes by considering the following recommendations:

Create a healthy workplace. A necessary first step involves establishing a code of conduct (or code of professionalism) that declares an organization’s intolerance of disrespectful behaviors and serves as a model for interdisciplinary collegial relationships (different but equal) and collaboration (mutual trust and respect that produces willing cooperation). Validate that mutual respect regardless of rank or status is an organizational core value. Use a standard communication process, such as SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) or TeamSTEPPS (Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety), to aid in streamlining critical information that must be shared, thus limiting the opportunity for disrespectful behaviors. For additional recommendations, review our newsletter article, Addressing disrespectful behaviors and creating a respectful, healthy workplace–Part II.

Reconcile medications. During care transitions (e.g., OR to postoperative unit, postoperative unit to ICU), a designated prescriber must review the patient’s medication orders, considering the patient's current condition and plans for care.

Bring medications to the bedside only when needed. Develop a policy that does not allow practitioners to bring a medication to the patient’s bedside until it is needed based on the prescribed order parameters (e.g., systolic blood pressure of greater than 130 mm Hg).

Conduct daily review of medications. Include a daily review of medications ordered and hanging on the patient's IV pole to determine if unneeded medications are ordered/present. Medications that are not needed should be immediately removed from the IV pole and discarded or returned to the pharmacy. We have previously shared risks with leaving unneeded medications at the bedside. For details, review our newsletter articles, Leaving a discontinued fentaNYL infusion attached to the patient leads to a tragic error and Risks with leaving discontinued infusions connected to the patient.

Trace infusion lines and confirm the programming. When infusions are started, reconnected, or changed (i.e., new bag/bottle/syringe), trace the tubing by hand from the solution container to the pump (and channel), to the connection port, and then to the patient to verify the proper infusion, pump/channel, and route of administration. Confirm that the infusion dose and rate are programmed accurately; verify that the order in the MAR and the medication label match what is programmed in the pump when performing line tracing before starting the infusion.

Promote a safe environment. Consider creating an “on-call” staffing model based on defined conditions (e.g., nurse-to-patient ratio, patient acuity metrics), that would allow nurse managers/leaders to review the situation, gather feedback from frontline staff, and have an action plan to divert or bring in additional resources, as needed. Encourage staff to speak up in situations where they feel that their workload and/or patient acuity is overwhelming or creating an unsafe environment in which an error may be more likely to occur. Ensure the physical environment offers adequate space and lighting and allows practitioners to remain focused on the medication-use process without distractions. For additional recommendations, review our newsletter article, Minimizing distractions and interruptions during medication safety tasks and Selected medication safety risks to manage in 2016 that might otherwise fall off the radar screen – Part II.

Manage similar-looking products. When the pharmacy receives a new product (e.g., new product added to the formulary, changes in manufacturer, during drug shortages), conduct a review to identify potential risks with the product’s design including any look-alike labeling and packaging concerns with other products on the formulary. When problems are recognized, consider purchasing the product (or one product of a problematic pair) from a different manufacturer. Also, inform staff who will be using the new product that it is being changed. For additional recommendations, review our previous article, Safety considerations during expedited product approval.

Educate staff. During orientation and ongoing training, review the organization’s policy on auto-programming, and removing medications from the bedside that are not needed. Stress the need to trace infusion lines and practice tracing lines during periodic simulations. Educate nurses about the availability of medications in ADC locations, including those that are available via override for urgent or emergent situations. Also, provide mandatory hospital-wide education for all staff about disrespectful behaviors on an annual basis. The purpose is to raise awareness of disrespectful behaviors and the problems they create. Communicate mutual respect as an organizational core value; motivate and inspire staff to help create a healthy workplace; articulate the organization’s commitment to achieving this goal; and create a sense of urgency around doing so. Measure the impact of this organizational training during annual culture surveys.

Use auto-programming. If your organization has implemented auto-programming of infusion pumps using interoperability, ensure its use is maximized. Nurse managers must have a system to monitor compliance and gather feedback from end users. Investigate instances where auto-programming was bypassed to understand barriers, correct system issues, and/or coach staff as needed. The organization that reported this event is planning to implement a data analytics tool that will generate reports for real-time compliance monitoring by nurse managers.

Monitor untraced lines. When a patient has an unanticipated event, adverse effect, or clinical deterioration, trace lines to investigate infusion misconnections.

Share good catches. Share impactful stories and recognize staff for good catches, including those caught through tracing the infusion line.

Suggested citation:

Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). Patient death after inadvertent infusion of PRN medication hanging on the bedside IV pole. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Acute Care. 2024;29(8):1-4.

Access this Free Resource

You must be logged in to view and download this document.