The Dark Side—Safety Issues When Protecting Medications from Light

Problem: The phrase, “protect from light,” is poorly defined in prescribing information and many drug references. Inconsistencies exist in understanding what “protect from light” means and the necessary measures that should be taken during the various phases of the medication-use process. ISMP recently researched this topic to "shed more light" on it for our readers. Our findings and recommendations are presented below.

Types of light vulnerabilities

There are different types of light (e.g., the visible spectrum, infrared, ultraviolet) that can affect pharmaceutical products. Certain medications, such as biologics, chemotherapeutics, and protein-containing and -derived products (e.g., vaccines, immune globulin) are particularly susceptible to wavelengths from ultraviolet or blue light. Medications that require prolonged intravenous (IV) infusion time are also most vulnerable to light.

Few medications need protection from light during administration

We recently searched Lexicomp monographs for “protect from light” and found more than 800 results mentioning the phrase—sometimes referring to when being stored, sometimes during administration, and sometimes specifically for both. Of those, less than 2% specified that protection from light was needed during administration.

Light protection testing

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for Industry: Q1A (R2) Stability Testing of New Drug Substances and Products, photostability testing is recommended during product development to determine appropriate manufacturing conditions and container closure systems. The FDA Guidance for Industry: Q1B Photostability Testing of New Drug Substances and Products further recommends that it may be appropriate to test certain products (e.g., infusions) to support their photostability in-use. However, this is left to the manufacturer's discretion. Medication labeling often does not provide adequate information on the duration of light exposure that may result in medication degradation to assist practitioners in determining if medications require protection from light exposure during specific parts of the medication-use process (e.g., administration).

Light protection responsibility

Several light-protective mechanisms exist, such as foil-shielding blister packaging, amber vials, overwrap bags, and tablet film coatings. Some of these mechanisms are put in place by the manufacturer, while in other cases, pharmacy or the practitioner administering the medication may need to implement them to limit light exposure during each applicable step in the medication-use process. Without specific information, medications that degrade with short exposure to light may not be sufficiently protected. On the other hand, overuse of light-protective containers (e.g., bags, overwraps) that hinder the practitioner’s ability to read the medication label, or other related processes (e.g., affixing labels with barcodes to the outer bag) can increase the risk of error.

Medication safety examples

Below are a few examples of medication safety issues reported to ISMP that involved protecting medications from light.

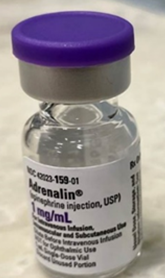

A patient who was undergoing surgery began decompensating due to vasodilation. The patient was given a dose of ADRENALIN (EPINEPHrine) from a 1 mg/mL injection vial, with no clinical effect. A practitioner noted that the vial used, along with several others, were discolored, indicating degradation of the product. EPINEPHrine solution is light sensitive and deteriorates rapidly when exposed to light, turning pink, and then brown. EPINEPHrine vials are available in clear glass that may not protect the medication from light (Figure 1). A subsequent dose was administered from a vial of EPINEPHrine that was not discolored with good clinical response.

A patient was prescribed a niCARdipine infusion to control blood pressure, but a norepinephrine infusion prescribed for a different patient was accidentally administered. The pharmacy dispensed both infusions in brown opaque bags to protect them from light. The pharmacy system was set up to print two patient-specific labels with barcodes; one to affix to the compounded infusion, and the other to be placed on the brown bag. At some point, the IV bags were accidentally switched. The nurse who inadvertently administered norepinephrine to the patient reviewed the label and scanned the barcode on the brown bag prior to administration but did not notice a different patient’s medication inside the bag. The patient recovered, but the organization reported that similar events have occurred.

Safe Practice Recommendations: Organizations should consider the following strategies to safeguard medications that need to be protected from light.

Develop a “protect from light” list based on phases that require light protection. Review prescribing information, published literature, and drug information resources to identify medications on your organization’s formulary that require protection from light during storage, preparation, and/or administration. Refer to resources such as Hospital Pharmacy’s Light-Sensitive Injectable Prescription Drugs—2022, which includes a comprehensive list of medications that require protection from light during specific steps of the medication-use process. Ensure there is a process to routinely review the list as manufacturers and prescribing information are continually modified and updated. Include this designation on monograph templates for new formulary requests.

Evaluate light-protective products and usage. Bags available to reduce the amount of light transmission to medications have various opacities. Consider purchasing products (e.g., amber bags) that meet the requirements for light protection but allow practitioners to read the medication label through the bag and still have visibility of the inner product for monitoring the infusion during administration. For medications that are recommended to be stored in the original carton to “protect from light” until preparation, consider using amber-lidded bins to contain the vials if the carton is to be disposed of on receiving (e.g., disposal of the carton before stocking due to USP <800> policy/procedure).

Label the product directly. Practitioners should scan the manufacturer's barcode directly on the product to prevent the risk of a false positive barcode scan from a pharmacy-applied or patient label. If a pharmacy-generated label with a barcode is needed (e.g., compounded infusion), affix it directly on the product (e.g., syringe, infusion bag). Do not include barcodes on pharmacy-generated labels placed on the outer containers or bags to force scanning of the product.

Additionally, for drugs that require protection from light, FDA should consider revising labeling to require more detailed information on the duration of light exposure that may result in medication degradation to ensure appropriate light protection of medications during the medication-use process.

Figure 1. Adrenalin (EPINEPHrine) 1 mg/mL injection by Par Pharmaceutical should be protected from light, but it comes in a clear vial.

Suggested citation:

Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). The dark side – safety issues when protecting medications from light. ISMP Medication Safety Alert! Acute Care. 2024;29(3):1-3.

Access this Free Resource

You must be logged in to view and download this document.