Personal Practice Changes Practitioners Would Make after Learning Firsthand about Medication Errors At ISMP

Awareness about medication errors and their causes prompts change. One lesson we have clearly learned is that the most effective strategies to prevent medication errors often lie outside the direct control of individual practitioners, particularly strategies related to technology, the environment, and the design of systems and processes. But there are many things individual practitioners can do in their own practice—changes in their behavioral choices when carrying out the tasks associated with medication use—to reduce the risk of a medication error.

During their experience at ISMP, students and fellows have seen firsthand the devastation that medication errors have wrought, and they know that medication errors could happen to them, too. We repeatedly hear that the experience at ISMP has changed their practice. ISMP staff and other practitioners associated with ISMP echo similar sentiments. More than 20 years ago, we asked ISMP nurses to share their thoughts about the personal practice changes that they would make if they returned to practice at the bedside. We did the same recently in January 2022, but this time we solicited answers to the following question from more than a dozen past and present ISMP fellows and staff: After being at ISMP, if you returned (or have returned) to frontline patient care, what three things would you do (or have done) differently? Described below are the top 10 changes practitioners would make (or have made) in their personal practice habits after learning firsthand about medication errors at ISMP. Three of the practice changes are the same as described by ISMP nurses more than 20 years ago: Make error reporting a priority, promote a Just Culture, and do not sacrifice safety for timeliness.

1. Make error reporting a priority. It is only through insightful information from those who have made errors that we learn about their underlying causes and strategies for prevention. Thus, reporting hazards, close calls, and other errors was a frequently cited priority for practitioners associated with ISMP. Some practitioners were very specific in their survey response, indicating that they would report more hazards and close calls, describe errors more fully in narrative reports, make it easier for staff to report errors internally, and follow-up more closely with the reporter. Many said they would actively seek feedback about reported errors or hazardous situations to spark change, as well as support colleagues who have made errors. Of course, practitioners would make (or have made) a commitment to report notable errors or potentially hazardous conditions externally to the ISMP National Medication Errors Reporting Program or the ECRI and the ISMP Patient Safety Organization. Everyone associated with ISMP knows firsthand how valuable it is to share “lessons learned” with others.

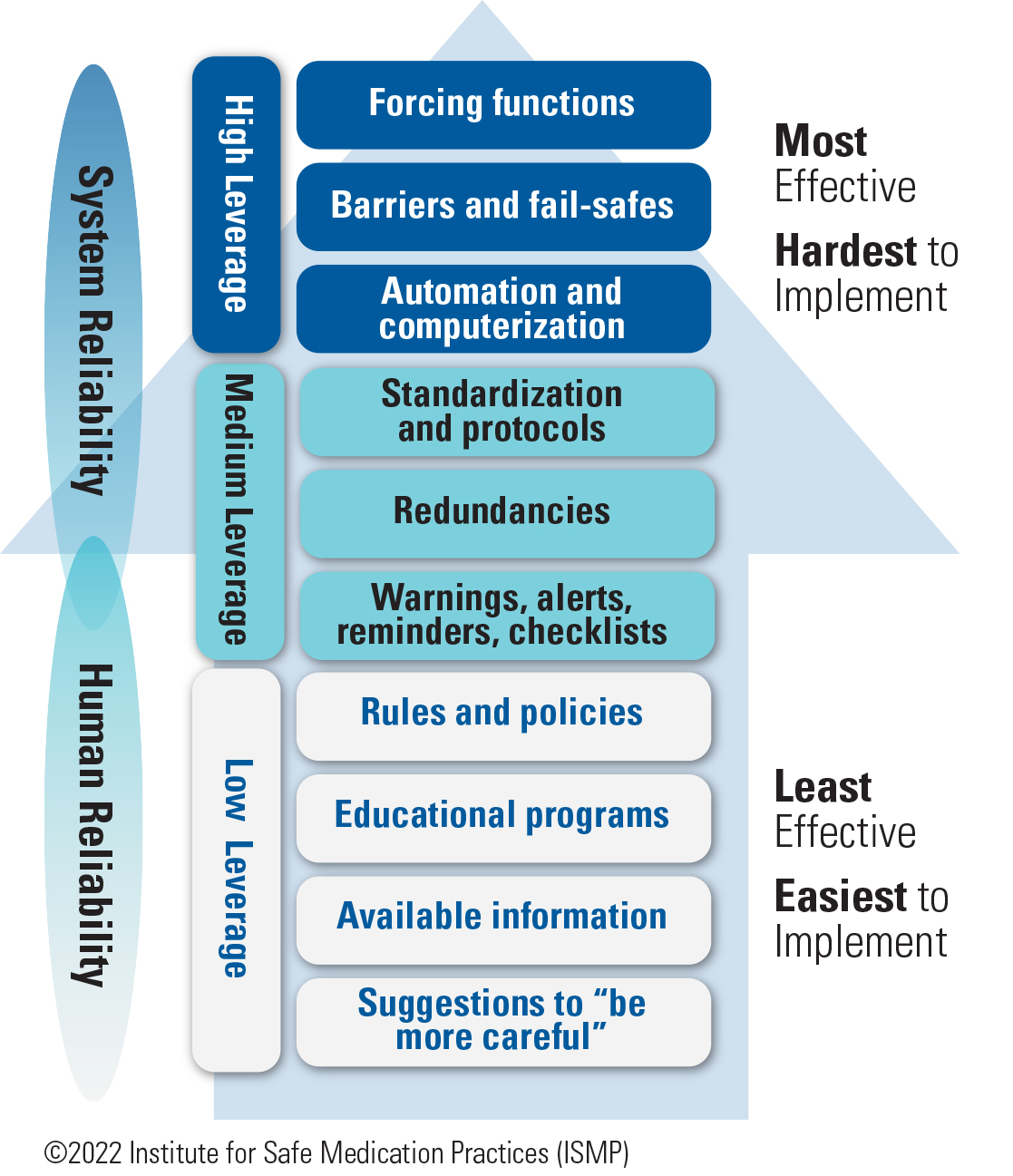

2. Fully utilize ISMP resources. Many practitioners associated with ISMP reported that they would utilize the ISMP newsletters as well as the quarterly Action Agenda more fully by bringing reports of errors that have occurred elsewhere to staff or safety meetings, discussing the likelihood of it happening at their practice site, identifying possible causes, and making suggestions for proactive prevention. Respondents also mentioned other specific ISMP resources, such as visiting the ISMP website more frequently to search for tools, resources, alerts, and services; implementing the ISMP Targeted Medication Safety Best Practices for Hospitals; utilizing the framework of the ISMP Key Elements of the Medication Use System (Assess-ERR Medication System Worksheets) to identify the contributing factors and underlying causes of medication errors; and referencing the ISMP Hierarchy of Error-Reduction Strategies (Figure 1).

3. Promote a Just Culture. Practitioners associated with ISMP expressed a sincere desire to work within a Just Culture. Recognizing the leadership-driven cultural transformation that must occur to truly implement and maintain a Just Culture (Part I; Part II), some practitioners provided unique examples of how they would pique (or have piqued) the interest of leadership to further explore what Just Culture could mean for their organizations and how it would help them achieve better outcomes:

-

Develop compelling medication safety presentations to help staff understand the tenets of a Just Culture

-

Hold discussions with leaders, human resources, and other influencers (e.g., medical staff leaders) to reach the tipping point for executive commitment to a Just Culture

-

Create a team of Just Culture champions

-

Be far more aware of at-risk behaviors and workarounds, get managers and leaders to collaborate with frontline staff to better understand the reasons for at-risk behavioral choices, implement high-leverage system changes based on these collaborations, and coach at-risk behaviors before errors result

-

Teach managers what good system design looks like and how to help employees make better decisions

4. Share risks with colleagues. Many practitioners associated with ISMP felt it was important to share known and suspected risks (hazards) with their colleagues to enhance awareness. For example, several pharmacists previously associated with ISMP had improved communication with prescribers upon returning to practice, noting they were no longer fearful about reaching out to prescribers to clarify unfamiliar or unusual orders. One practitioner pointed out that he often shares known or suspected risks with other practitioners in person, asking them if they were aware of the risk and if they have any ideas for improvement. Another practitioner noted that she had taken pictures of problematic packaging and sent them to internal colleagues as well as to ISMP. Still another practitioner noted that her organization now uses a dashboard and shares data about clinical risks with all levels of the organization.

5. More comprehensive event investigation. Many practitioners associated with ISMP would develop (or have developed) investigative depth behind why human errors, at-risk behaviors, and reckless behaviors occur, uncovering the deep system-based causes of events, or latent failures. These practitioners said they would try to steer clear of the common pitfalls when conducting an event investigation. For example, they would avoid making assumptions and instead investigate all questions or concerns, and they would routinely employ systems thinking, always searching for upstream factors that contributed to the event. During event investigation, one practitioner said she now identifies each phase of the medication-use process that could be involved in or affected by an error or hazard, and then targets each of these phases for risk-reduction strategies.

6. Develop safety teams. If they returned to practice, numerous practitioners said they would establish (or have established) a team of medication safety champions in key clinical units specifically to support medication safety priorities. The team would conduct daily safety huddles with unit staff to update and engage managers in medication safety priorities and to uncover safety gaps as well as successes. The team would also participate (or has participated) in weekly Patient Safety Leadership WalkRounds (Frankel A. Patient safety leadership WalkRounds. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2004) to learn about patient safety issues and the culture. Another resource, Positive Leadership WalkRounds (Sexton JB, Adair KC, Profit J, et al. Safety culture and workforce well-being associations with Positive Leadership WalkRounds. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47[7]:403-11) was mentioned by one survey respondent as a way to learn about patient safety issues or successes, targets for special recognition, staff work-life balance, and the burnout climate.

7. Advocate for a full-time Medication Safety Officer (MSO). Several practitioners associated with ISMP told us they would seek out an MSO position if they returned to practice, and a few prior ISMP practitioners noted they had advocated for a full-time MSO in their organizations. One practitioner hoped to change the MSO reporting structure from the pharmacy to an executive leader. When healthcare executives empower the MSO to act on medication safety concerns, and position them on the organizational chart where it will best enhance their ability to affect change, it helps to ensure that the organization will identify and learn from medication risks and errors (both internal and external), and implement high-leverage strategies to reduce or eliminate the negative consequences of medication errors.

8. Do not sacrifice safety for timeliness. Several practitioners said, when they returned to practice, they no longer considered timeliness to be the most important dimension of drug dispensing or administration. While it is clearly important to start drug therapy as soon as possible, often the clinical need for quick dispensing and administration does not outweigh the safety of having a pharmacist review the order first. One practitioner said she no longer rushes the drug administration process (or refers to it as a “med pass” because it is so much more than just “passing” medications). She is now more realistic about the pharmacy turnaround time for routine medications and, when able, waits for the pharmacy to prepare and dispense intravenous (IV) solutions. Another practitioner noted that he would no longer rush the drug administration process, especially when handling high-alert medications.

9. Involve an executive champion. If they returned to practice after working at ISMP, several practitioners thought it would be critical to find a champion in medication safety among the upper executive leadership team (e.g., chief nursing officer, medical staff officer) who would help facilitate medication safety goals, especially if they received pushback. The support and confidence of a well-respected executive leader are essential to the infrastructure of a successful medication safety program as well as to the proactive adoption of organization-wide medication safety initiatives and technology.

10. Conduct targeted education to staff and patients. After being at ISMP, several practitioners told us they would provide targeted education to new staff members, including students and residents, about critical medication safety initiatives in each phase of the medication-use process, particularly when using high-alert medications. One practitioner said he would team with risk management to present targeted training programs based on past hazards, errors, and claims. Another practitioner, a pharmacist, would provide patient counseling more frequently in community pharmacies; instead of asking patients whether they have any questions for the pharmacist, she would counsel all patients who pick up a new prescription.

Conclusion

Our greatest teachers are practitioners who have made medication errors and have shared their experiences with others, including ISMP—they are our primary source of inspiration for change. Every day, each fellow, nurse, pharmacist, and physician at ISMP learns from practitioners who have bravely and altruistically shared their stories. These stories help ISMP clearly see the system vulnerabilities and uniquely understand why practitioners make errors and make risky choices while attempting to remedy a system problem. We hope the insight from our past fellows and the current ISMP staff is an inspiration for change for our readers, too.

Access this Free Resource

You must be logged in to view and download this document.